How To Serialize?

Every byte can represent 256 possible values. We can represent 256^2 = 65536 possible values with 2 bytes, 256^3 = 16777216 possible values with 3 bytes, and so on. There are many ways to interpret these bytes depending on context which is the key to serialization. All serialization does is turn information into data, in this case datatype instances to buffers. If used smartly, less data can be used to represent the same information which is what Squash exploits as much as possible.

Cursors

Buffers themselves are statically sized, which means that when a buffer is created it cannot be resized to fit more data. Squash uses something called a Cursor which wraps around buffers to treat them like dynamically sized stacks. This means users push and pop data off of the stack, and if it grows too big the buffer gets reallocated behind the scenes. Every serializer expects a cursor to push and pop from when serializing and deserializing. For more information, the internally used cursors have been extracted into a dedicated library called Cursor.

A fun consequence of using a stack is that multiple independent serializations are allowed on the same cursor in succession. This makes fine-tuned serdes a breeze, since a user can serialize a number, then a string, then an array of vectors, and it just works!

Booleans

In Luau, the boolean type is 1 byte large, but only 1 bit is actually necessary to store the contents of a boolean. This means we can actually serialize not just 1, but 8 booleans in a single byte. This is a common strategy called bit-packing to implement bit-fields.

| Happy | Confused | Irritated | Concerned | Angry | Humber | Dazed | Nage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

All of this information fits inside a single byte! We can use this to serialize 8 booleans in a single byte.

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.boolean().ser(cursor, true)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.boolean().des(cursor))

-- true false false false false false false false

local cursor = Squash.cursor(3)

Squash.boolean().ser(cursor, true, false, true, false, true, true, false, true)

Squash.print(cursor)

--- Pos: 1 / 3

--- Buf: { 181 0 0 }

--- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.boolean().des(cursor))

-- true false true false true true false true

Numbers

In Luau, the number type is 8 bytes large, but only 52 of the bits are dedicated to storing the contents of the number. This means there is no need to serialize more than 7 bytes for any kind of integer.

Unsigned Integers

Unsigned integers are whole numbers that can be serialized using 1 to 8 bytes.

N = { 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, . . . }

They may only be positive and can represent all possible permutations of their bits. These are the easiest to wrap our heads around and manipulate. They are often used to implement Fixed Point numbers by multiplying by some scale factor and shifting by some offset, then doing the reverse when deserializing.

| Bytes | Range | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | { 0, 1, 2, 3, . . . , 253, 254, 255 } | 0 | 255 |

| 2 | { 0, 1, 2, 3, . . . , 65,534, 65,535 } | 0 | 65,535 |

| 3 | { 0, 1, 2, 3, . . . , 16,777,214, 16,777,215 } | 0 | 16,777,215 |

| . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| n | { 0, 1, 2, 3, . . . , 2^(8n) - 2, 2^(8n) - 1 } | 0 | 2^(8n) - 1 |

WARNING: Using 7 or 8 bytes puts uints outside the 52 bit range of representation, leading to inaccurate results.

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.uint(1).ser(cursor, 243)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 243 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.uint(1).des(cursor))

-- 243

local cursor = Squash.cursor(1)

Squash.uint(1).ser(cursor, -13)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 1

-- Buf: { 243 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.uint(1).des(cursor))

-- 243

local cursor = Squash.cursor(4, 1)

Squash.uint(2).ser(cursor, 7365)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 3 / 4

-- Buf: { 0 197 28 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.uint(2).des(cursor))

-- 7365

Signed Integers

Signed Integers are Integers that can be serialized with 1 through 8 bytes:

Z = { ..., -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ... }

They use 2's Compliment to represent negative numbers. The first bit is called the sign bit and the rest of the bits are called the magnitude bits. The sign bit is 0 for positive numbers and 1 for negative numbers. This implies the range of signed integers is one power of two smaller than the range of unsigned integers with the same number of bits, because the sign bit is not included in the magnitude bits.

| Bytes | Range | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | { -128, -127, . . . , 126, 127 } | -128 | 127 |

| 2 | { -32,768, -32,767, . . . , 32,766, 32,767 } | -32,768 | 32,767 |

| 3 | { -8,388,608, -8,388,607, . . . , 8,388,606, 8,388,607 } | -8,388,608 | 8,388,607 |

| . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| n | { -2^(8n - 1), -2^(8n - 1) + 1, . . . , 2^(8n - 1) - 2, 2^(8n - 1) - 1 } | -2^(8n - 1) | 2^(8n - 1) - 1 |

WARNING: Using 7 or 8 bytes puts ints outside the 52 bit range of representation, leading to inaccurate results.

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.int(1).ser(cursor, 127)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 127 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.int(1).des(cursor))

-- 127

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.int(1).ser(cursor, -127)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 129 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.int(1).des(cursor))

-- -127

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.int(1).ser(cursor, 128)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 128 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.int(1).des(cursor))

-- -128

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.int(1).ser(cursor, -128)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 128 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.int(1).des(cursor))

-- -128

Floating Point

Floating Point Numbers are Rational Numbers that can be represented with either 4 or 8 bytes:

Q = { ..., -2.0, ..., -1.0, ..., 0.0, ..., 1.0, ..., 2.0, ... }

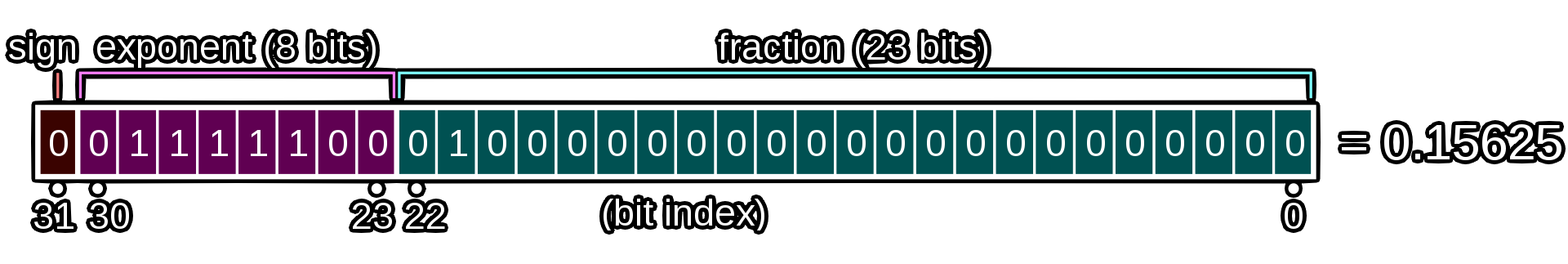

With 4 bytes (called a float), the possible values that can be represented are a bit more complicated. The first bit is used to represent the sign of the number, the next 8 bits are used to represent the exponent, and the last 23 bits are used to represent the mantissa.

The formula for calculating the value of a float from its sign, exponent, and mantissa can be found at this wikipedia article.

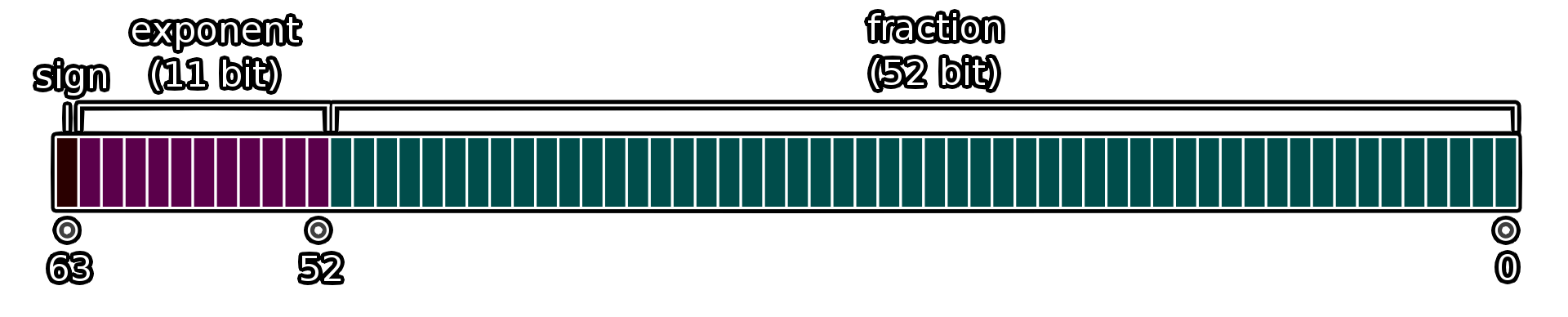

With 8 bytes (called a double). The first bit is used to represent the sign of the number, the next 11 bits are used to represent the exponent, and the last 52 bits are used to represent the mantissa.

The formula for calculating the value of a double from its sign, exponent, and mantissa can be found at this wikipedia article.

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.number(4).ser(cursor, 174302.923957475339573)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 4 / 8

-- Buf: { 187 55 42 72 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.number(4).des(cursor))

-- 174302.921875

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.number(8).ser(cursor, -17534840302.923957475339573)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 8 / 8

-- Buf: { 34 178 187 183 161 84 16 194 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.number(8).des(cursor))

-- -17534840302.923958

Variable Length Quantities

Sometimes we don't know how many bytes we need to represent a number, or we need to represent a number so large that 8 bytes isn't enough. This is where VLQs come in. They are a binary format to represent arbitrarily large numbers as a sequence of bytes. 7 bits encode the number, 1 bit encodes the end of the number. This means 127 serializes to 1 byte. 128 serializes to 2 bytes. It increments by powers of 128 instead of 256 like bytes do because of the missing bit.

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.vlq().ser(cursor, 10)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 138 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.vlq().des(cursor))

-- 10

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.vlq().ser(cursor, 130)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 2 / 8

-- Buf: { 129 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.vlq().des(cursor))

-- 130

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.vlq().ser(cursor, 547359474)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 5 / 8

-- Buf: { 130 5 0 21 114 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.vlq().des(cursor))

-- 547359474

Ranges

A range is a custom datatype that encodes an integer inverval [a, b] using uints with as few bytes as possible. This is great if you know your lower and upper bounds for array sizes or other lists. It is not strict and will technically encode outside of bounds.

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.range(100, 150).ser(cursor, 130)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 30 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.range(100, 150).des(cursor))

-- 130

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.range(1, 15).ser(cursor, 16)

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 16 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.range(1, 15).des(cursor))

-- 16

Strings

Strings are a bit trickier conceptually since they have a variable size. However to serialize with Squash is actually easier than numbers! Every character is a byte, so it is useful to think of strings are arrays of bytes. After writing each character in sequence, we need a mechanism to count how many characters we've serialized else we'll never know when to stop reading when deserializing. Right after the string, the length is serialized as a Variable Length Quantity to use only necessary bytes.

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.string().ser(cursor, "Hello, World!")

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 14 / 18

-- Buf: { 72 101 108 108 111 44 32 87 111 114 108 100 33 141 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.string().des(cursor))

-- Hello, World!

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

Squash.string(13).ser(cursor, "Hello, World!")

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 13 / 18

-- Buf: { 72 101 108 108 111 44 32 87 111 114 108 100 33 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(Squash.string(13).des(cursor))

-- Hello, World!

Using Base Conversion

There are many ways to compress serialized strings, a lossless approach is to treat the string itself as a number and convert the number into a higher base, or radix. This is called base conversion. Strings come in many different flavors though, so we need to know how to serialize each flavor. Each string is composed of a sequence of certain characters. The set of those certain characters is called that string's smallest Alphabet. For example the string "Hello, World!" has the alphabet " !,HWdelorw". We can assign a number to each character in the alphabet like its position in the string. With our example:

{

[' '] = 1, ['!'] = 2, [','] = 3, ['H'] = 4, ['W'] = 5,

['d'] = 6, ['e'] = 7, ['l'] = 8, ['o'] = 9, ['r'] = 10,

['w'] = 11,

}

This allows us to now calculate a numerical value for each string using Positional Notation. The alphabet above has a radix of 11, so we can convert the string into a number with base 11. We can then use the base conversion formula, modified to work with strings, to convert the number with a radix 11 alphabet into a number with a radix 256 alphabet such as extended ASCII or UTF-8. To prevent our numbers from being shortened due to leading 0's, we have to use an extra character in our alphabet in the 0's place that we never use, such as the \0 character, making our radix 12. Long story short, you can fit log12(256) = 2.23 characters from the original string into a single character in the new string. This proccess is invertible and lossless, so we can convert the serialized string back into the original string when we are ready. To play with this concept for arbitrary alphabets, you can visit Zamicol's Base Converter which supports these exact operations and comes with many pre-defined alphabets.

local x = 'Hello, world!'

local alphabet = Squash.string.alphabet(x)

print(alphabet)

-- !,Hdelorw

local y = Squash.string.convert(x, alphabet, Squash.string.utf8)

print(y)

-- >q#�

print(Squash.string.convert(y, Squash.string.utf8, alphabet))

-- 'Hello, world!'

local y = Squash.string.convert('great sword', Squash.string.lower .. ' ', Squash.string.utf8)

print(y)

-- �zvFV�

print(Squash.string.convert(y, Squash.string.utf8, Squash.string.lower .. ' '))

-- 'great sword'

local y = Squash.string.convert('lowercase', Squash.string.lower, Squash.string.upper)

print(y)

-- LOWERCASE

print(Squash.string.convert(y, Squash.string.upper, Squash.string.lower))

-- lowercase

local y = Squash.string.convert('123', Squash.string.decimal, Squash.string.binary)

print(y)

-- 1111011

print(Squash.string.convert(y, Squash.string.binary, Squash.string.octal))

-- 173

print(Squash.string.convert(y, Squash.string.binary, Squash.string.decimal))

-- 123

print(Squash.string.convert(y, Squash.string.binary, Squash.string.duodecimal))

-- A3

print(Squash.string.convert(y, Squash.string.binary, Squash.string.hexadecimal))

-- 7B

print(Squash.string.convert(y, Squash.string.binary, Squash.string.utf8))

-- {

Literals

Literals are individual values that can be enumerated and distinguished using just u1s. This is useful for encoding enums of names, orientations, and other unique identifiers with minimal data.

local literal = Squash.literal("a", 2, "c", true, "e")

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

literal.ser(cursor, "c")

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 1 / 8

-- Buf: { 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(literal.des(cursor))

-- "c"

Arrays

Arrays are a classic table type {T}. Like strings, which are also arrays (of bytes), after serializing every element in sequence we append a VLQ representing the count. An array can store an array or any other table type.

local arr = Squash.array

local float = Squash.number(4)

local myarr = arr(float)

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

myarr.ser(cursor, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5.5, 6.6, -7.7, -8.9, 10.01})

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 37 / 40

-- Buf: { 0 0 128 63 0 0 0 64 0 0 64 64 0 0 128 64 0 0 176 64 51 51 211 64 102 102 246 192 102 102 14 193 246 40 32 65 137 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(myarr.des(cursor))

-- 1 2 3 4 5.5 6.599999904632568 -7.699999809265137 -8.899999618530273 10.01000022888184

local arr = Squash.array

local float = Squash.number(4)

local myarr = arr(float, 8)

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

myarr.ser(cursor, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5.5, 6.6, -7.7, -8.9, 10.01})

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 32 / 40

-- Buf: { 0 0 128 63 0 0 0 64 0 0 64 64 0 0 128 64 0 0 176 64 51 51 211 64 102 102 246 192 102 102 14 193 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(myarr.des(cursor))

-- 1 2 3 4 5.5 6.599999904632568 -7.699999809265137 -8.899999618530273

Maps

Maps are a classic table type { [T]: U } that map T's to U's. A map can store a map or any other table type.

local u = Squash.uint

local vec3 = Squash.Vector3

local vec2 = Squash.Vector2

local mymap = Squash.map(vec2(u(2)), vec3(u(3)))

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

mymap.ser(cursor, {

[Vector2.new(1, 2)] = Vector3.new(1, 2, 3),

[Vector2.new(4, 29)] = Vector3.new(4, 29, 33),

[Vector2.new(72, 483)] = Vector3.new(72, 483, 555),

})

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 40 / 40

-- Buf: { 43 2 0 227 1 0 72 0 0 227 1 72 0 33 0 0 29 0 0 4 0 0 29 0 4 0 3 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 0 2 0 1 0 131 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(mymap.des(cursor))

-- {

-- [Vector2(24346692898)] = 72, 483, 555,

-- [Vector2(243466928B0)] = 4, 29, 33,

-- [Vector2(243466928C8)] = 1, 2, 3

-- }

T

If using the TypeScript port of Squash this is irrelevant, but for Luau users, the type system is not powerful enough to take a table of serializers and infer the correct type. To get around this, the Squash.T function maps SerDes<T> -> T and returns what you give it. It's an identity function that lies about its type.

local T = Squash.T

typeof(Squash.number(4))

-- SerDes<number>

typeof(T(Squash.number(4)))

-- number

print(Squash.number(4) == T(Squash.number(4)))

-- true

Records

Records (Structs) { prop1: any, prop2: any, ... } map enumerated string identifiers to different values, like a named tuple. Because all keys are string literals known ahead of time, none of them have to be serialized! A record can store a record or any other table type.

When defining compound types the code can become verbose and difficult to read. If this is an issue, it is encouraged to store each SerDes in a variable with a shorter name.

local T = Squash.T

local u = Squash.uint

local vlq = Squash.vlq()

local bool = Squash.boolean()

local str = Squash.string()

local float = Squash.number(4)

local vec2 = Squash.Vector2

local arr = Squash.array

local map = Squash.map

local opt = Squash.opt

local record = Squash.record

local playerserdes = record {

position = T(vec2(float)),

health = T(u(1)),

name = T(str),

poisoned = T(bool),

items = T(arr(record {

count = T(vlq),

name = T(str),

})),

inns = T(map(str, bool)),

equipped = T(opt(str)),

}

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

playerserdes.ser(cursor, {

position = Vector2.new(287.3855, -13486.3),

health = 9,

name = "Cedrick",

poisoned = true,

items = {

{ name = 'Lantern', count = 2 },

{ name = 'Waterskin', count = 1 },

{ name = 'Map', count = 4 },

},

inns = {

['The Copper Cauldron'] = true,

Infirmary = true,

['His Recess'] = true,

},

equipped = nil,

})

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 90 / 90

-- Buf: { 0 9 1 72 105 115 32 82 101 99 101 115 115 138 1 84 104 101 32 67 111 112 112 101 114 32 67 97 117 108 100 114 111 110 147 1 73 110 102 105 114 109 97 114 121 137 131 130 76 97 110 116 101 114 110 135 129 87 97 116 101 114 115 107 105 110 137 132 77 97 112 131 131 67 101 100 114 105 99 107 135 1 51 185 82 198 88 177 143 67 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(playerserdes.des(cursor))

-- {

-- ["health"] = 9,

-- ["inns"] = ▼ {

-- ["His Recess"] = true,

-- ["Infirmary"] = true,

-- ["The Copper Cauldron"] = true

-- },

-- ["items"] = ▼ {

-- [1] = ▼ {

-- ["count"] = 2,

-- ["name"] = "Lantern"

-- },

-- [2] = ▼ {

-- ["count"] = 1,

-- ["name"] = "Waterskin"

-- },

-- [3] = ▼ {

-- ["count"] = 4,

-- ["name"] = "Map"

-- }

-- },

-- ["name"] = "Cedrick",

-- ["poisoned"] = true,

-- ["position"] = 287.385498, -13486.2998

-- }

Tuples

Tuple types (T...) are like arrays but not wrapped in a table, and each element can be a different type. Tuples cannot be used in table types, and cannot be nested in other tuples.

local S = Squash

local T = S.T

local mytuple = S.tuple(

T(S.Vector3(S.number(8))),

T(S.CFrame(S.int(1))),

T(S.BrickColor()),

T(S.EnumItem(Enum.HumanoidStateType))

)

local cursor = S.cursor()

mytuple.ser(cursor, Vector3.new(123456789, 1, 0), CFrame.new(1, 2, 3), BrickColor.new(93), Enum.HumanoidStateType.Freefall)

S.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 40 / 40

-- Buf: { 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 240 63 0 0 0 96 52 111 157 65 1 0 0 64 64 0 0 0 64 0 0 128 63 194 0 134 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(mytuple.des(cursor))

-- 123456792, 1, 0 1, 2, 3, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1 Medium stone grey Enum.HumanoidStateType.Freefall

Tables

Luau tables are extremely versatile data structures that can and do implement every other kind of data structure one can think of. They are too versatile to optimally serialize in the general case, which is why Squash has the previously listed Array, Map, and Record serializers.

Only use this serializer if you cannot guarantee the shape of your table beforehand, as it offers less control and worse size reduction. This is the algorithm that Roblox uses when serializing tables because they can't guarantee the shape of the tables users pass. If you do not know the type of your table but you still need to serialize it, then the Squash.table serializer is a last resort.

It has to store data for every value, the type of every value, every key, and the type of every key, which makes it significantly larger than the specialized functions. It also does not offer property-specific granularity, instead only letting you map types to serializers for both keys and values alike.

local serdes = Squash.table {

number = Squash.number(8),

string = Squash.string(),

boolean = Squash.boolean(),

table = Squash.table {

CFrame = Squash.CFrame(Squash.number(4)),

Vector3 = Squash.Vector3(Squash.int(2)),

number = Squash.vlq(),

},

}

local cursor = Squash.cursor()

serdes.ser(cursor, {

wow = -5.352345,

[23846.4522] = true,

[false] = 'Gaming!',

ThisWontSerialize = DateTime.now(),

[{

CFrame.new(-24.2435, 2, 3), CFrame.new(), Vector3.new(354, -245, -23),

[100] = Vector3.zAxis,

[Vector3.zero] = 255,

}] = {

[1] = CFrame.identity,

[2] = Vector3.zero,

[3] = 256,

},

})

Squash.print(cursor)

-- Pos: 131 / 135

-- Buf: { 71 97 109 105 110 103 33 135 1 0 2 240 162 175 32 205 104 21 192 0 119 111 119 131 1 1 2 208 68 216 240 156 73 215 64 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 129 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 130 0 130 0 0 131 0 131 3 1 0 0 64 64 0 0 0 64 176 242 193 193 1 129 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 130 0 233 255 11 255 98 1 2 131 0 129 127 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 228 0 133 3 132 0 0 0 0 }

-- ^

local buf = Squash.tobuffer(cursor)

local cursor = Squash.frombuffer(buf)

print(serdes.des(cursor))

-- {

-- ["wow"] = -5.352345,

-- [23846.4522] = true,

-- [Table(24BE4A11A98)] = ▼ {

-- [1] = 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1,

-- [2] = 0, 0, 0,

-- [3] = 256

-- },

-- [false] = "Gaming!"

-- }